A Piece of Meat: Symbol of Power and Masculinity?

Saida Nuralieva

Imagine a farm beef steak with rosemary roasted potatoes or a Greek salad with greens, olives and feta cheese. What would you choose?

There is a notion that women prefer lighter vegetable based foods to maintain their physique, while men try to eat more meat, perhaps instinctively wanting to build more muscles. Even if meat does not promise us an athletic body, we sincerely believe that binging on animal-based protein brings us closer to what is commonly called good nutrition. Still, more often than not, we choose food not based on our nutritional needs, but on the emotions it elicits.

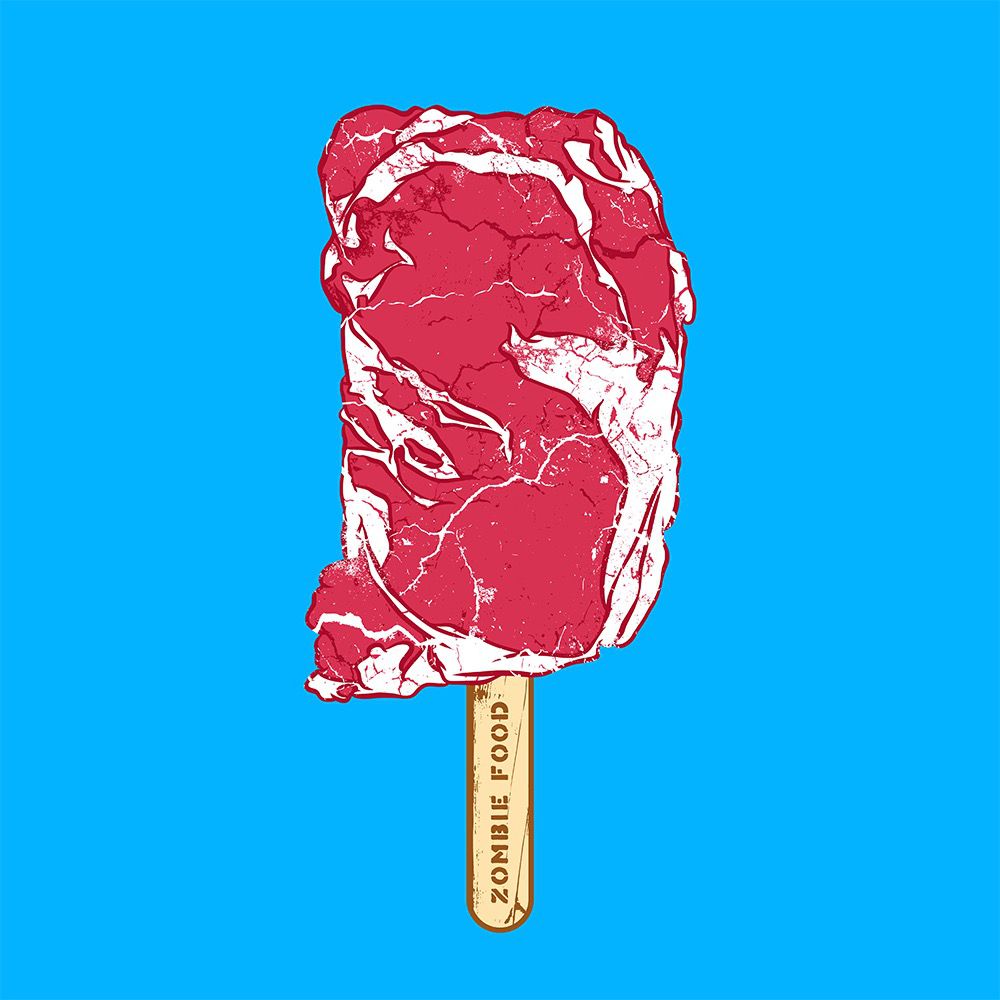

In the Scorpion’s well-known song "Another Piece of Meat" the main character compares the soloist of the band with "another piece of meat". Often, this wording is used to denote sexually attractive subjects and it is often used to increase sales. Marketers use the term "foodporn" to reinforce the association with satisfaction from the taste of food. Historian Warren Belasco explores this phenomenon that has emerged in modern vocabulary. In his book "Food: Key concepts", he raises the question: "If baking, sugar, fat, meat and salt are so closely tied to the most enjoyable experiences of life, who would want to reduce their consumption?“

Even in everyday life, one can notice that eating is somehow a social status or a tool for maintaining relationships. In Kyrgyz culture pieces of meat from different parts of the animal carcass indicate the authority of a person, his gender and age. For example, in the village of At-Bashi in Naryn oblast until the middle of the 19th century, mutton head was served only to elders. They would cut off a small piece of meat, taste it, and pass the rest on to the younger ones, as a symbol for investing in the future.

Until today, in traditional meal ceremonies, each guest is given pieces of mutton meat - "zhilikter" - corresponding to his social position or kinship degree. The sheep‘s head is never served to a woman. There is a custom to leave a small piece of meat to the hosts’ children - "ustukan", and at the bottom of the „tabak“ (large plate) there must be left a small amount of "turagan et" - "sliced meat", "keshik" for women serving at the event. The token gestures on the gatherings assume the presence of a woman in the kitchen, and men next to the fire, meanwhile, all the "dastorkon" (food on the table) is for the "konoktor" (guests) otherwise you can be called inhospitable hosts, and even run into gossip.

Sociologist Brenda Bigan, in her scientific publication "Food is culture, but it’s also power", notes that while most women agree that cooking in the Armenian community was mandatory for women and created an instrument of oppression, many also claim that their mothers and grandmothers had authority and control in their kitchens, which often became a place where they were bonded with other women. As some studies show that women seldom cook for themselves, but rather for their families - especially the men in the family - and risk not meeting their nutritional needs.

Food consumption is also inextricably linked to the maintenance of good health, as food somehow affects the well-coordinated functioning of the human body. Professor John Olive's research on “Men food and prostate cancer Gender influences on mens diets” suggests that while a healthy diet can contribute to longevity and better health, only few of the men in treatment for prostate cancer are making dietary changes to improve their health. In the treatment of prostate cancer, medical procedures can cause disorders of reproductive health and potency of the patients. In order to preserve their own masculinity and gender relations, most of those treated could not give up their usual "masculine" meat diet in favour of a vegetable diet.

Feminist and vegan Carol Adams, who wrote the book "Sexual Politics of Meat", believes that meat defines the hierarchical dominance of "man over nature" and "man over woman”. In her opinion, meat remains one of the symbols of masculinity. Adams desсribes:

"I saw a portrait of Henry VIII, eating steak and beans, on the wall of the restaurant. On the other side of the room there were portraits of his six wives. Catherine of Aragon was holding an apple in her hand. Duchess Mar was depicted with a turnip, Anne Boleyn with a red grape, and Jane Seymour with a blue grape. Finally, Katharina Parr was next to the cabbage. None of the women were eating steak or anything meat, no meat was on the table in front of them."

Those with power - typically males - “have always eaten meat,” Adam wrote, while the rest of society - women, children, people of color, whoever is considered second-class in the culture have had to make do with what’s left. As a result, meat became a symbol of power.

In general, it can be argued that the stereotype of a direct relationship between meat and masculinity is widespread, but its manifestations vary in culture. Understanding the nuances will help combat it more effectively. Meat occupies a central part in the Kyrgyz diet and an honorable place on the table. It seems that traditions of cutting meat which are celebrated with music and fireworks are especially prominent in Central Asia compared to the rest of the world.

The food production system has changed, as has our lifestyle: most people live in cities in comfortable conditions and work in confined spaces. Food is produced in large quantities and abundantly available in stores. Therefore, traditional ideas about diet need to be revisited. However, the public consumption of meat is still one of the main indicators of one’s position in society, for which there is a constant struggle. WHO global statistics show that excessive consumption of red meat is a significant factor in a number of serious health complications, especially in older age categories.

Knowing all of this, the questions we must ask ourselves now: is the traditional model of eating meat worth the health risks? Am I choosing meat as proof of masculinity and associated social status?